Understanding the past informs the present

Music is not composed in an historical and cultural vacuum, and therefore should not be performed in an historical and cultural vacuum – that is to say, with no understanding of the musical language of the composer and the time and place in which he lived.

Performers are “time travelers”

It is interesting to note that composers – or artists of any kind – reflect the spirit of the time and place in which they live (or lived), as well as their social, cultural and artistic environment. Performers, on the other hand, while subject to the spirit and time in which they live are nevertheless not restricted to that specific time and space, but are free to travel through time and space as they perform music written over a span of 400+ years in a great variety of countries and cultures.

But what does this “time travel” imply for us as performers? Can we take our cultural environment – and the performance practices it has engendered – with us and still hope to comprehend and savor the great variety of musical expression that has come down to us over the centuries? I am reminded of a line in Somerset Maugham’s play, “The Perfect Wife”: the wife says of her husband, “Edward is perfectly happy to travel anywhere in the world as long as there is absolutely nothing that will remind him that he is not in England.”

Do we not sometimes perform the music of Bach or Schubert or Brahms or Debussy with the mind-set of our own period? While we all wish to play inspired performances, it is an informed inspiration that we should aspire to.

How do we do this? To begin with, we have to shed the idea of what C.S. Lewis calls “the arrogance of progress”. How often have you heard someone say, “if only Bach knew what we know today, he would have wanted his music to sound this way.” What arrogance. It is true that in certain areas of science and technology progress is an upward curve, but this cannot hold true for artistic creation. Picasso’s paintings are not better than Rembrandt’s or Michaelangelo’s – they are just different. They reflect a mind and artistic personality which is very much the product of the time and place in which he lived. The same is true for Rembrandt and Michaelangelo in their own ways. Now no one, I hope, would propose that we take the paintings of these two great masters of the 16th and 17th centuries and re-work them to make them in the style of Picasso – and then call it “progress”. But don’t we do the same thing when we perform the great masterpieces of the past with a technique which is rooted in, and limited to, the technique of the 20th and 21st centuries?

Think about our colleagues in the world of acting. Great actors are able to depict a variety of characters in plays and films ranging over a wide span of time and place. To do this successfully, they have to immerse themselves in the world of their character – the time, the place, the culture, the mentality. This requires research and study on their part, but in doing so they are able to take on the character of the person they are to depict so convincingly that we can’t imagine him as anyone else (though we may have seen him in quite different roles in the past). Should we not, as musical performers, do the same?

Now since this series of master classes is devoted primarily – though not exclusively – to performance practices in the Baroque and Classical eras (that is to say, the 17th and 18th centuries), I would like to turn our focus to that period and see what it has to tell us about musical performance.

Assumptions:

We all live with assumptions. If I were to tell you the best route to take from Santa Barbara to, say, Pasadena, I would likely say, “take the 101 to the 126 to the 5 to the 210”, and if you lived in this area you would understand what I meant. But to someone from another part of the world, or even to someone living here 100 years ago, it would be a meaningless jumble of numbers. Or take our modern computer talk: to someone 50 years ago and it would be a foreign language – much of it is even to people of my generation (!). Assumptions “assume” that the person you are communicating with is so conversant with a body of knowledge, and the language that expresses it, that elaboration is unnecessary.

So what assumptions did 17th and 18th composers make about the performance of their music? And what did they find unnecessary to elaborate on or be explicit about?

To begin with, we need to understand that music composed in these centuries was not written with performers of the 21st century in mind. It was written, in the case of Bach, for next Sunday’s church service (I speak here of the cantatas), or, in the case of Haydn, for Count Esterhazy’s next social gathering – in both cases the composers were writing for performers they worked with daily. Very little of Bach’s music was published in his lifetime, so it is doubtful that he had future performers in mind – it was written for the performers he worked with on a day-to-day basis. The same is true of Haydn until the last decades of his life.* If they were not writing for some future generation, but for their day-to-day colleagues, what does this tell us about how we should approach the performance of their music – and the music of the other composers of the Baroque and Classical eras? What clues does this give us about the assumptions 17th and 18th century composers made?

Secondly, it is important to bear in mind that in this period most composers were also performers – two sides of the same coin – so they thought it not only unnecessary, but improper to intrude on the artistic insights of the performer. Again, we are talking about a period when music was written not for future generations, but most often for immediate consumption by performers who were only too well aware of – in fact, steeped in – the assumptions of the time, i.e., performers who spoke the musical language of the composer and shared the same assumptions. (Leaving aside, for the purpose of brevity, the clash between the French Style and the Italian Style in the 18th century – an important topic for performers, but one best left for another day.)

So what did 17th and 18th century composers take for granted in their communication with their performing colleagues?

1. Dynamics and Expression

Dynamics provide contrast, shading and, in general, contribute to the overall expressiveness of the music. But, if not specifically indicated, they are left as a matter of choice on the part of the performer. He or she may choose to drop the dynamic level of a repeated phrase to give an echo effect – or play it even louder to make it more forceful. He or she may decide the final statement of a section or movement (perhaps a post-cadential extension) should be played louder to make a statement or drive the point home, or played softer to create the effect of a gentle “farewell”.

In the 17th and 18th centuries these choices, for the most part, were left up to the performer – possibly out of respect for the performer’s own artistic role – but also based on the assumption that the performer understood the spirit of the music in the same way the composer did. The composer’s role was to provide the notes and, increasingly as the 17th century moved into the 18th century, to give limited instructions as to tempo or character – this was especially true in the case of dance movements, each dance having its own well-understood step and nature, familiar to anyone living in that culture. But, beyond this, it was left up to the creative judgment of the performer to inject the expressive nuances in the music.

At this point I would like to quote from the Harvard Dictionary of Music (1944 Edition) on the term “expression” in music:

Expression may be said to represent that part of music which cannot be indicated by notes or, in its higher manifestation, by any symbol or sign whatsoever. It includes all the nuances of tempo, dynamics, accent, touch, phrasing, bowing, etc., by which the mere combination and succession of pitch-time values is transformed into a living organism. Although as far as written notes are concerned, the performer is strictly bound to the composer’s work, he enjoys a considerable amount of freedom in the field of expression, which may be said to represent the creative contribution of the performer.

Nowhere was this more true than in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Although some may insist that the absence of dynamics and other markings proves that Baroque music was to be played “square” and without expression – more like a mathematical equation (ignoring’ of course, that the art and architecture of the same period is “romantic”, often to the point of voluptuousness) – thankfully, the vast majority of performing artists see these works as great masterpieces, rich with opportunities for expression.

Quoting again from the same article in the Harvard Dictionary: as the 18th century progressed, “composers more and more felt the necessity of providing at least some basic indications, in order to clarify their intentions and to prevent mistakes or arbitrariness on the part of the performer.” (op. Cit.)

We see this reaching an early culmination in the compositions of Beethoven, who left tradition behind – and with it the assumptions it held – as his music became more and more a personal statement and increasingly full of dynamic and other indications.

2. Ornaments

Baroque and Classical composers assumed that performers would “grace” their music with a variety of ornaments: trills, mordents, appogiaturas, turns, slides and, interestingly, vibrato (more on this later). The trick was to do this in good taste (Geminiani wrote a book entitled, “The Art of Playing in a True Taste”) – and this is something which we, traveling backwards in time from this century, have to give a great deal of time and thought to.

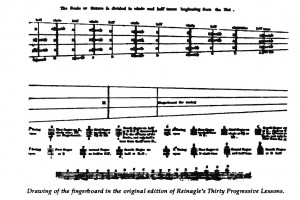

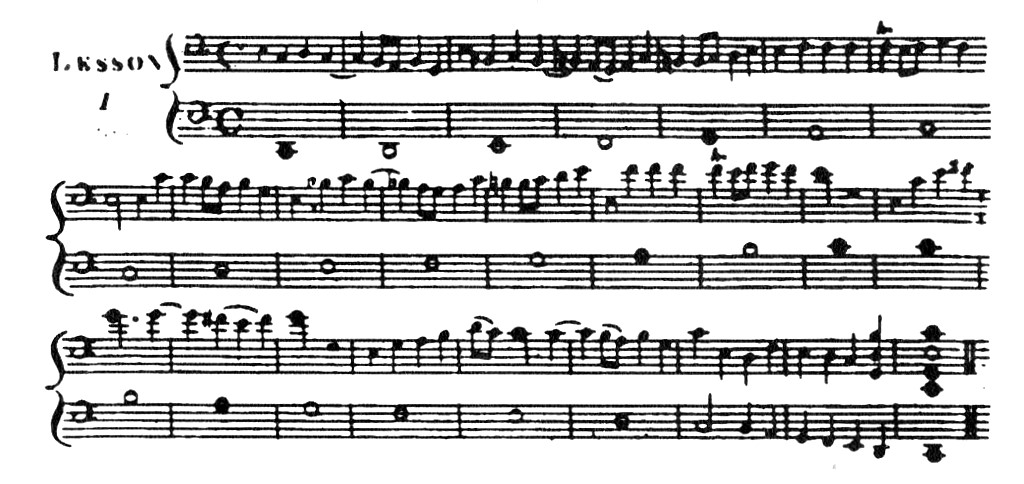

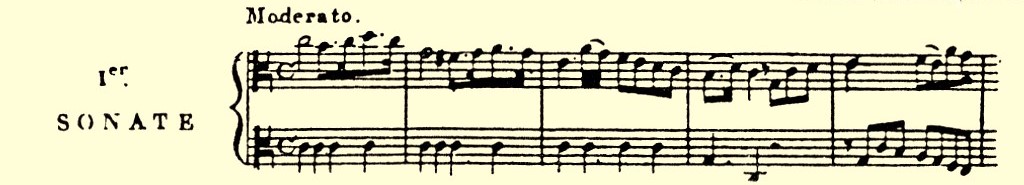

Corelli, a contemporary of J.S.Bach and one of the greatest violinists of his time, was so famous for his embellishments of his music that he finally relented and published an edition of his Op. 5 sonatas which contained his ornamentation. As you will see, they are quite elaborate when you compare them with the original publication.

(insert picture)

Improvisation and cadenzas were also considered a form of ornamentation (Tartini includes them in his Treatise on Ornamentation). Improvisation is an art that fell into general disuse in the 19th century. When it returned in the 20th century, it was mainly in jazz music. In the Baroque and Classical eras it was assumed that when the performer came to a fermata at the close of a section or movement he would view it as an open invitation to extemporize. However, this extemporizing was not arbitrary – there were certain basic rules which were laid out for the performer to follow – another assumption. Tartini devotes several pages in his treatise to cadenzas and provides skeletal harmonic outlines for playing them, varying from the simple to the very elaborate. He then illustrates various ways in which these skeletons can be fleshed out by the performer (again, we see that the line of demarcation between composer and performer is much more blurred than it is today).

What do all these assumptions imply for us as performers? The obvious conclusion is that composers at this time assumed that performers, steeped in the same tradition, would know what was expected of them – in essence, performers would speak the same language as the composer and understand his intent and know what they should bring to the music. We cannot hope to travel to their time and place if we insist on bringing with us the baggage of our time and place (as useful and proper as it might be for the music of our time) – to be willing to time travel as long as we will not be required to do anything that will remind us that we are not in the 21st century, to paraphrase Somerset Maugham.

Sound production

And here we come to the most important assumption of all: sound production. This is really something which goes so far beyond the word “assumption” that I prefer to call it sound concept. “Concept” implies that which is conceived – or, I would add, conceivable.

Who of us can tell what music will sound like 300 years from now? 200 years? Even 100 years? Can we conceive that? We can only travel backwards in time.

Now we come again to that phrase, “If only Bach had known what we know…” . Well, he didn’t. And he couldn’t – any more than we can know what music – and the instruments that produce it will sound like 300 years from now. He wrote for the instrumental sounds he knew – his music was conceived with those instruments in mind and molded to suit their nature and capacity.

So what was their nature and capacity? If you play a Baroque violin or cello – or have heard one, you will know that the sound of the Baroque instrument is gentler, warmer – more like candle light – and with perhaps a greater capacity for subtle nuance. The “modern” violin or cello (at times an early 18th century instrument modified to have a higher bridge and thus more tension on the instrument) has a bigger sound – it is bolder and more projecting. One could say it is more like an electric light – or a laser beam.

Now what led to this change, this transformation? The usual reasons given are that concert halls became bigger in the 19th & 20th centuries, or that orchestras are much larger today than they were in the 18th century. But these reasons don’t really stand up if you stop to think about them. I have sat at the back of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles and listened to Segovia play his guitar – unmiked – and heard every note clearly. More recently, the Academy of Ancient Music performed here in Santa Barbara at the Grenada Theater and the sound of their Baroque instruments – the same instruments Bach would have composed for – carried beautifully to the back of the theater. So the size of the hall doesn’t seem to be the reason. What about the size of the orchestra? Well, if you have an 18th century orchestra of say eight 1st and 2nd violins, six violas and four cellos and then expand that to twenty 1st and 2nd violins, ten violas and eight cellos the sound will be louder, of course, because there are more instruments, but the balance will be the same.

So what was the reason for converting 18th century instruments (a process, incidentally, which happened only gradually over several decades) to the more powerful “modern” instruments? The answer, in my opinion, lies in our old friend, the piano – or, to give it its original name, the pianoforte – or fortepiano.

Prior to the introduction of the piano on the musical scene, the predominant keyboard instruments were the harpsichord and the organ. Both instruments, however, had one characteristic – some would say limitation – and that was their inability to move gradually from one dynamic level to another. In other words, to crescendo and diminuendo became an important aspect of expression. Now the string and wind instruments – and, of course, the human voice – had no problem with this. Indeed, it was their nature. But the harpsichord and organ could only change dynamic levels by changing the stop, with no graduation of dynamic level in between possible. It was left to an unassuming cousin of the harpsichord – the clavichord – to provide the solution.

The clavichord, that little church mouse of the keyboard instruments, had an extremely limited dynamic range – but it had the capacity to move gradually from one dynamic level to another depending on how hard one struck the keys. Out of this quiet, unassuming instrument the concept of the pianoforte was born in the mid-18th century. Bach saw one and played it shortly before he died and was impressed by it.

But it is the subsequent development of the pianoforte that interests us here, because it’s development (once the dimensions of the length of the keyboard had been established) can be summed up in one word: louder. Nearly every change made to the piano in the ensuing 150 years was to increase its sound. Now I know that’s an over-simplification, but the fact is that the piano grew in size and volume until it became the instrument we know today.

The reason that this is important, especially for string players, is that in the course of the 19th century the piano became our principal playing partner – in sonatas, piano trios, piano quartets, quintets. As the piano grew in volume, string players began to look for ways to increase the volume of their instruments. The solution lay in raising the height of the bridge to create greater tension on the instrument. In order to accommodate this greater height, the neck was canted back so that the angle of the fingerboard could parallel the angle of the strings. So that, in a nutshell – at least in my opinion – is how we came to have the “modern” violin. Whether this new sound as it gradually evolved influences the music composed for it – or the other way around – I will leave for you to decide. For now, let us go back to the sound of the instruments Bach and his contemporaries were writing for.

Sound is our medium – it is to us what oils or water colors or acrillics are to painters, or wood or marble or clay are to sculptors. We “paint” in sound. Sound is the only medium through which we communicate our thoughts – our musical thoughts – to others. As we have seen, sound production and the sound ideal have changed throughout the centuries. There isn’t a better or a worse in this. There is no “progress” from a more primitive sound to a more sophisticated sound. There is just a difference.

This difference is what is critical to us as performers – as “time travelers”. If we wish to play the great masterpieces of, say, Bach or Mozart in the way these composers envisioned it, we are going to need some understanding of the sound ideal they were composing for – and the sound of the instruments Bach and his contemporaries composed for was a warmer, richer sound. It was more capable of subtle nuance than the modern instruments and, in the Classical period much cleaner and more pure. So when we play the music of these earlier masters, we should want to recreate as best we can – even with our modern instruments – the sound the composer had in mind.

How do we do this? The easiest way, of course, is to avail ourselves of a period instrument and let it teach us. We will soon learn what it can and can’t do. It can’t, for instance, produce the volume and boldness of its modern equivalent. You will soon learn its limitations in that direction – it won’t let you force it. But it will show you subtleties of color and nuance you hadn’t even imagined. Because of the lessened tension on the strings you will find that you can often take fast movements much faster than on the later instruments. Conversely, slow movements can work even better at slower tempi than we can play them on the modern instruments.

Most importantly, you may find, as I did, that playing on period instruments broadens your technique and enlarges your musical perspective and tone color palette. The so-called limitations (by modern standards) of these instruments opens doors to new sound concepts and interpretation – sound concepts and interpretations which we can use to inform our performance of early music even on our modern instruments.

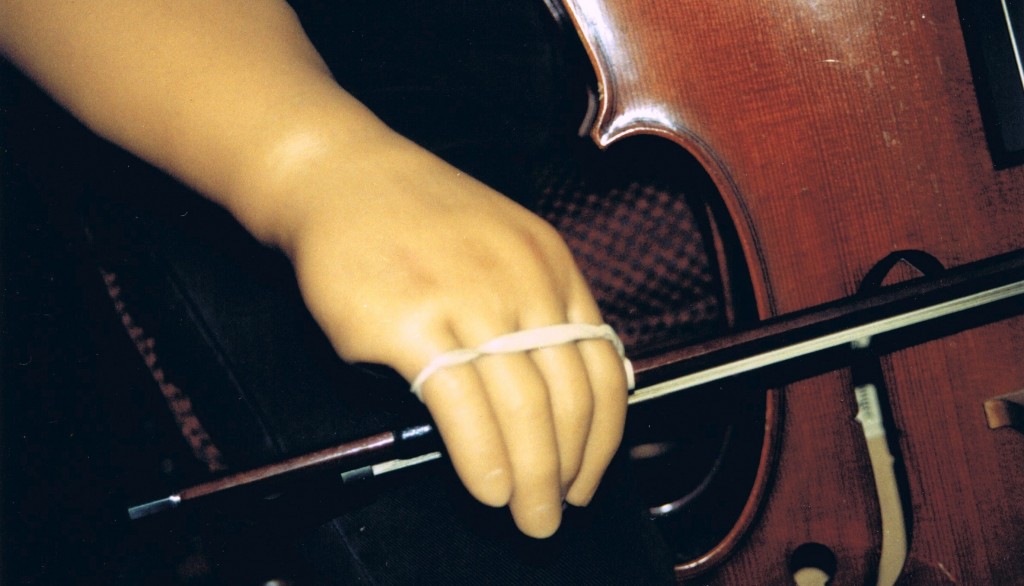

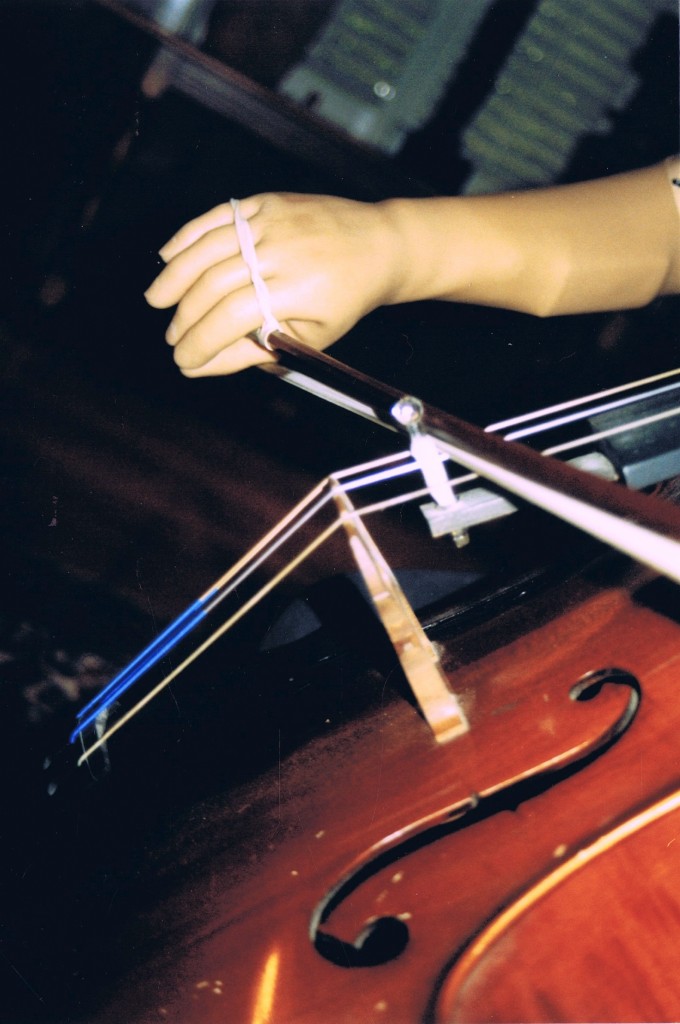

Here I have been speaking primarily to string players, and I realize that most do not have access to period instruments. But even playing with a bow from the period has worlds to teach you – and access to Baroque bows is much easier to come by. It is certainly a good first step, and an easy way to get started and to get a glimpse into another world of playing.

To close, I would like to draw your attention to the enormous influence the 17th and 18th centuries have had on subsequent centuries – including our own. These are the centuries that gave us the opera, the symphony, the string quartet (as well as string duos and trios), piano duos, trios, quartets and quintets, fantasias, the fugue, dance movements like the minuet, the sonata form, the ABA song form, and all the instrumental groupings we take for granted today. It is small wonder that Leonard Bernstein called the 18th century the “golden century”.

**************

* Of course there was an increasing amount of published music as the 18th century wore on, which implies a broader performing public, but it was, I believe, not so much with an eye to posterity as an eye to a broader dissemination of the composer’s music – and, no doubt, with the composer’s eye to a bit of additional income (music publications in the later decades of the 18th century frequently carry on the cover “Printed for the Author and sold at…”.)