By Nona Pyron

The 18th century, that veritable cauldron of musical styles and innovation, is becoming more and more alive for us today as we come face to face with the vast scope of its musical literature. As we sift through the 8,000 Baroque and Classical works in the Grancino Collection, we are continuously astonished by the wealth of string music suitable and/or intended for pedagogical use. And the more we delve into this 18th century string literature, the more impressed we have become by this seemingly endless treasure trove of teaching material.

As a cellist, my involvement has been principally with the repertoire for cello, and here there are rich pasture indeed. Cello sonatas and duos in the Baroque and Classical eras, intended principally for home and concert performance, run the gamut from the simplest of basso continuo lines to virtuoso compositions demanding skills on a level of, say, the Roccoco Variations. Through this literature a series of easily managed stepping stones is provided to bring beginners right through to the virtuoso level, and cellists of all levels of ability are well served.

Much the same can be said for the literature of the violin and viola. It is important also to remember that in the 17th and 18th centuries the delineation between the various instruments within a family was not as sharp as today: in the 18th century a tutor for violin – or a set of variations to develop bowing – would have been legitimate fodder for cellists as well, and violinists were not above playing the continuo line.

The Sonata as Teaching Material

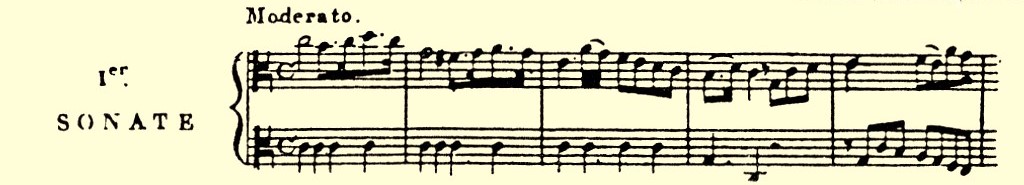

One of the most common forms of instrumental chamber music in the 18th century was the sonata, or “solo”, for two lines of music – the bottom line usually serving as the basso continuo line, though not infrequently performed purely as a duo line. Intended for concert and home use, this essentially “duo” literature provided a wide variety of music for players at all levels of development. 18th century pedagogues were aware of the potential dual purpose of the music, and we find in various sources (Geminiani, The Art of Playing in a True Taste, among others) instructions to cellists in the early stages of learning to look to the continuo lines as the most fertile of learning fields, both for technical advancement as well as the development of musical sensitivity (and, needless to say, for the sheer pleasure of playing chamber music at a very early stage) – and then to the upper (solo) line to stretch their techniques.

Music Specifically Intended for Teaching Purposes

Some performer/teachers in the 18th century undertook to organize a step-by-step presentation of musical material for the benefit of beginning players, and in so doing provided us with some of the most useful teaching material of any period.

The starting point was often the most basic rudiments of music: meter, rhythm, clefs, and, of course, how to hold the instrument and the bow. Then scales were introduced in conjunction with duets of increasing difficulty and length (to be played, presumably, with the teacher and/or friends) until the beginner was led through a series of painless and musically satisfying steps to a mastery of the instrument.

Cello Tutors

Over the years I have been involved with this 18th century music, four cello tutors have caught my attention. I have used them extensively in my own teaching (it is no accident that they were the first to be published by Grancino) and would like to discuss them in some detail here.

1. Joseph Reinagle: Thirty Progressive Lessons for the Violoncello (1800)

In the opening pages Reinagle touches briefly on the following subject:

Of the Names and length of the different Notes…

Of the Rests, and Dots…

Of Sharps, Flats and Natural…

Of Repeats and Slurs…

Of Expressing notes tied different ways…

Of Shakes…

Of Appogiaturas…

Of Common, Triple and Compound time…

On all the Cliffs [clefs] used on the Violoncello…

On Tuning the Instrument…

On Holding the Violoncello…

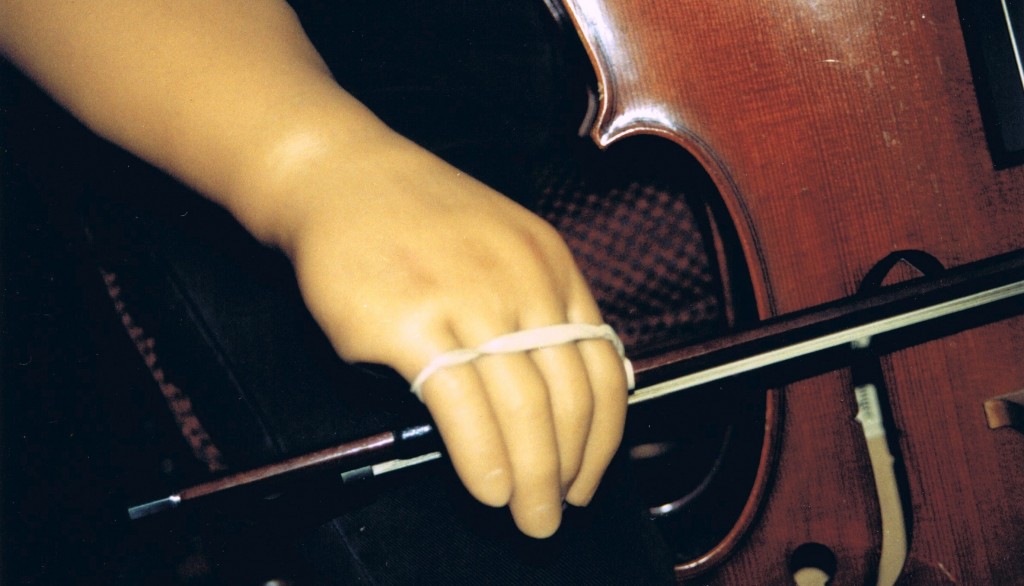

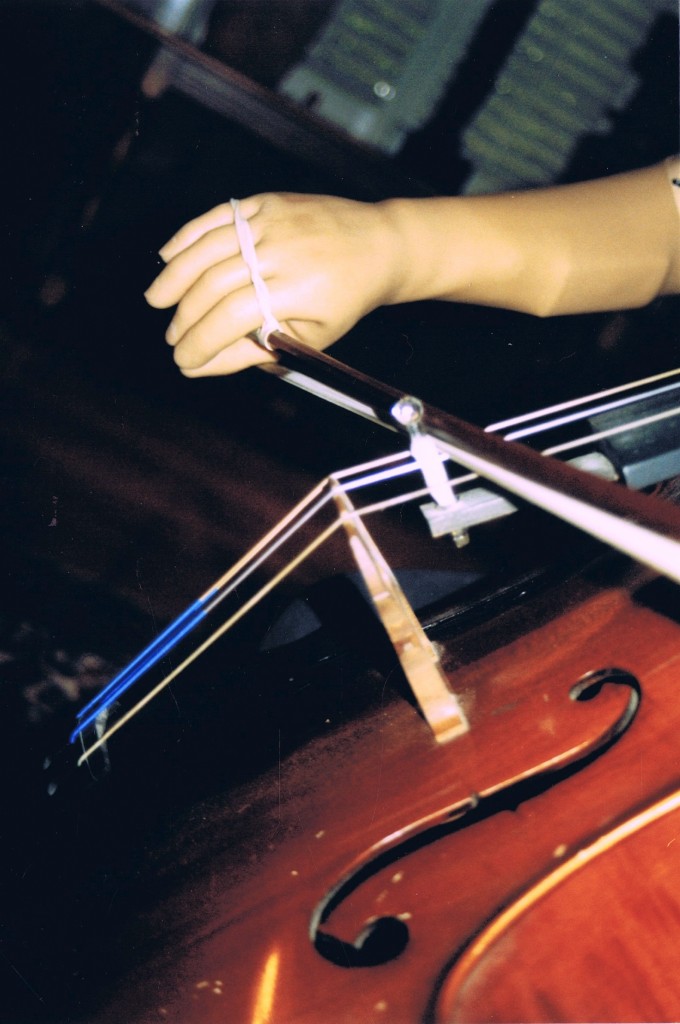

On Bowing…

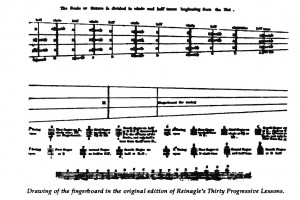

Of interest in this section is a drawing of the fingerboard indicating the location of the notes on it.

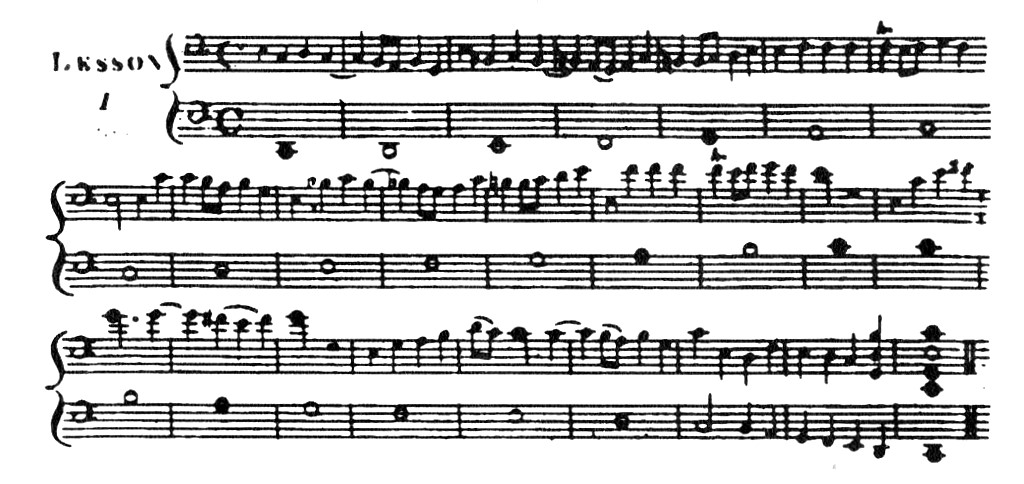

He then proceeds to “The first lesson on Playing…” and prefaces it with the following comment: I recommend the following lessons to begin with, instead of playing over the scale so frequently, as it usually done, by beginners, by which means, the learner will arrive at a knowledge of the notes with more pleasure to himself, and also, in a shorter time. I have affixed the scale at the beginning of each page, in order to enable the learner to find the notes readily.

Lessons I to VI (each four to six lines of music in length) afford the beginner an opportunity to become familiar with the notes of the first two octaves of the C major scale in various rhythmic and melodic arrangements.

Beginning with Lesson VII, All lessons are in the form of duos, frequently imitative in nature. Thus the beginner develops both technically and musically by playing with the teacher and assimilating from the teacher, almost unconsciously, the correct rhythm, intonation, bowing articulations and musical phrasing. Both lines being of equal difficulty, each lesson affords a double opportunity for learning within a given melodic and rhythmic context. Most important, the drudgery of the early stages of learning is bypassed and the pupil is introduced very early on to the joys of real music making… after all, they took up the cello in order to enjoy making music, so why not let them get at it right from the start? I used this book myself for teaching years prior to its publication and can personally attest to its usefulness in bringing pupils of all ages rapidly and happily through the early stages of playing.

Although the scales (from Lesson VII onward) all extend up through the fourth position, the lessons themselves stay within first position. By Lesson XVII double stops are introduced and the duets continue to develop in complexity. After Lesson XX, studies in 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th positions are introduced, as well as “Exercises” in three and four flats and five sharps. At this point the pupil is also given hints at improvisation through a series of “Preludes” which replace the former scales. These I would highly recommend to anyone wishing to take the first steps toward improvisation on the cello.

The book ends with an exercise in double stops, followed by arpeggiated variations of the same chords; and a series of bowing variations on a melodic passage. By this time the pupil, a solid foundation for his playing well in hand, is ready to move on to the challenges of the myriad compositions awaiting him in the 18th century repertoire. His 20th century counterparts will find that this book has not only given them a reliable foundation upon which to extend their Baroque and Classical techniques, but an excellent springboard into the diverse demands of Romantic and Modern music (which, after all, grew out of the foundations laid in the 18th century).

2. Oliver Aubert: Exercises or Studies for the Violoncello

The full title of this marvelous tutor is: Exercises or Studies for the violoncello… / “Consisting of three Parts / Part 1 / Thirty-two Lessons constructed on the Gamut in different Keys & Exercises for the use of the Thumb. / 2nd / Three progressive Duos / 3rd / Three Practical Solos / The whole is designed for the study of the different Cliffs & General Improvement of the Pupil.”

This book, which works well in conjunction with Reinagle, launches the pupil from the very first line into the act of music making in a most marvelous way: as the pupil plays a C major scale in whole notes, the teacher plays a melody above which transforms what might otherwise be a tedious scale into a true participation on the creation of a musical performance. It also transforms the usual flat-footed slogging through a slow scale into (in the musical pupil) a sensitive reaction to the overall music it is helping to create. What a wonderful way to begin playing the cello!

On the first page this same “duet” is presented three times: first time with the upper line in bass clef, next (an octave higher) in tenor clef and lastly (of importance in the 18th century, but less today) in transposed treble clef. Although these clefs have little relevance for the beginning pupil, he or she has nevertheless been exposed to the idea at the appropriate time. (the “appropriate time” for Aubert comes as early as Lesson 4 for the tenor clef, and Lesson 6 for the transposed treble clef, assuming the pupil chooses to play the upper lines in the duets as well.)

In general these duets progress much more rapidly and go much farther than the Reinagle in their technical scope (hence the advantage in combining them with the Reinagle). Part I ends with eight exercises in thumb position plus a Rondo utilizing the newly acquired thumb techniques. The Duos in Part II and the Sonatas in Part III increase the technical demands on the cellist far beyond the level of “beginner” and, if pursued and mastered, will render him capable of tackling most works in the 18th century repertoire.

3. Anon.: A New and Complete Tutor for the Violoncello (c.1770)

As with the Reinagle, this tutor begins with a wealth of general information on the basics of music. It then commences a series of duets, all suitable for players in the early stages of development, arranged for two cellos from what must have been the current “hit tunes” of the era.

Finally, I would like to consider one additional 18th century cello tutor because of its very unusual approach:

4. Jean Stiastny: Il Maestro ed il Scolare

This unique tutor combines lessons on the cello with lessons in composition, and does it rather well. The first part, quite simply written for both cello lines, is a series of imitations – starting at the unison and progressing through to the octave. This is followed by six pieces with fugues, also in the form of duets, which are more extended works and technically more demanding. In the 18th century, when composition went much more hand-in-glove with performance than it does today, these must have been valuable lessons indeed for instilling in the budding performer some of the basic steps toward contrapuntal writing. It may be that we in the 20th century have something to learn here.

Viola Tutors

Anon.: Complete instructions for the Tenor (c.1790)

As with the Reinagle, the Anonymous Complete Instructions for the tenor [viola], published in London around 1790, attempts a boot-strap operation for budding violists. On the title page the intent is clear: “Complete Instructions for the Tenor Containing such Rules and Example as are necessary for Learners, with a selection of Favorite Song-tunes, Minuets, Marches etc. – Judiciously adapted for that Instrument by an Eminent Master”. And, again similar to the Reinagle, it contains five pages of instructional text (of interest to 20th century students seeking insights into 18th century performance practices) and in full-size fold-out fingerboard chart.

The use of duos of graduated difficulty appears again in a viola tutor by J. Martinn: Methode pour l’Alto-Viola which is comprised of twelve lessons and three sonatas in the form of duos for two viola (ostensibly pupil and teacher).

The Art of Bowing on the Violin

In considering the foundations of technique, mention must be made of the considerable number of works intended to expand bowing technique. These usually bear the title “Variations” or “The Art of Bowing” and are typically written for the violin (though, in keeping with the performance practices of the 18th century, cellists and violists would have felt free to make use of them). One recently released Grancino Editinos is “The Art of Bowing on the Violin” by Joseph Gehot. The title continues: …“calculated for the Practice & Improvement of Juvenile Performers” and the Material is laid out in a very practical way to achieve the stated aim.

Another work in this vein (soon to be released by Grancino Editions) is the 100 Variazioni per Esercizio del Violino by Wenceslaw Pichl. First published in Florence and Naples in 1787, subsequent publications in London, Berlin and Amsterdam attest to the popularity of this study work. The editor, Robin Stowell, writes in the preface that “each brief (eight bar) variation is devoted to an executive problem of technique or style. Sometimes this is identified in the text; e.g., variations 51 & 57 feature harmonics; 55 is to be played smoothly (liscio); 59 is in gypsy style (alla zingarese); 65 is una corda; 66 is marked zoppicando (literally “limping”).

What all of these tutors have in common is the admirable habit of sugar coating the early stages of learning via musically interesting duets which introduce the musical experience into the learning process at a very early stage – a very healthy kind of bribery! It was assumed that the pupil would bring the duos to his lessons and, by playing them through with his teacher, gain a doubly valuable learning experience. But they also had the additional bonus of being available for him or her to play with any musical friends or family. And, of course, it was but a small step from the study duos to the genuine performance repertoire of the day (in fact, in many duos of the period the line between the two is often blurred). We have no equivalent of this in our modern repertoire, but perhaps there is no reason why we should: the cellistic techniques and musical language of the 18th century are the foundation of all that has come since, so what better place to start?